Summary: Using a unique longitudinal dataset collected from primary school students in Pakistan, we document four new facts about learning in low-income countries. First, children’s test scores increase by 1.19 SD between Grades 3 and 6. Second, going to school is associated with greater learning. Children who dropout have the same test score gains prior to dropping out as those who do not but experience no improvements after dropping out. Third, there is significant variation in test score gains across students, but test scores converge over the primary schooling years. Students with initially low test scores gain more than those with initially high scores, even after accounting for mean reversion. Fourth, conditional on past test scores, household characteristics explain little of the variation in learning. In order to reconcile our findings with the literature, we introduce the concept of “fragile learning,” where progression may be followed by stagnation or reversals. We discuss the implications of these results for several ongoing debates in the literature on education from Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs).

New Evidence on Learning Trajectories in a Low-Income Setting

Natalie Bau

Jishnu Das

Andres Yi Chang

Citation: Bau, Natalie, Jishnu Das, and Andres Yi Chang. 2021. "New Evidence on Learning Trajectories in a Low-Income Setting". International Journal of Education Development, 84: 1-26.

Many children in low-income countries cannot read a full sentence or perform basic mathematical operations, such as addition, after spending 5-6 years in primary school. The drivers of low learning remain unclear because of the lack of the high-quality, longitudinal test score data needed to understand how children learn. This paper uses one of the first such datasets to uncover new facts about how children learn in a low-income setting.

The Learning and Educational Achievement in Pakistani Schools (LEAPS) dataset, assembled by Tahir Andrabi, Jishnu Das and Asim Ijaz Khwaja, is used for the analysis. The LEAPS dataset follows more than 12,000 children as they progress from 3rd to 6th grade and are among the first data from a low-income setting to allow us to examine children’s test scores in a consistent manner across four years. The data are from Punjab province, Pakistan (the 12th largest schooling system in the world). The fact that Pakistan scores similarly to other low-income countries in internationally benchmarked tests suggests that the patterns in these data may be equally applicable elsewhere. In each year between 2003 and 2006, the LEAPS study tested children using tests designed in consultation with pedagogical and education experts in the subjects of English, Urdu, and Mathematics. The norm-referenced tests covered a wide range of concepts and capabilities in order to track how children learned over time. Each test retained a rotating core of “linking items,” so that some questions were repeated from year to year. These linking items allow us to calibrate all the tests on a common scale, following established methods in the literature on Item Response Theory.

Study Design and Findings

Children do learn in every grade between grades 3-6 as measured by improvements in subject knowledge over time

Unsurprisingly, children do learn in every grade. For instance, 58% of children could correctly multiple “4 x 5” in grade 3, and this fraction then increases to 60%, 73% and 79% in each subsequent year. We see similar patterns across every question and subject, and an aggregate measure of learning (which can be placed on the same scale across tests using item response theory) shows that test scores increase by 1.2sd between grades 3 and 6. This relative rate of learning is similar to what we find in the Young Lives countries of Vietnam, Peru, India (Andhra Pradesh) and Ethiopia and also to the U.S. state of Florida, all of which have gains of approximately 1 standard deviation over a similar 4-year period. This implies that in all these school systems the top 30% of children in grade 3 score (roughly) the same as the bottom 30% of children in grade 6. It does not imply that they learn the same amount since the tests and starting learning levels are very different.

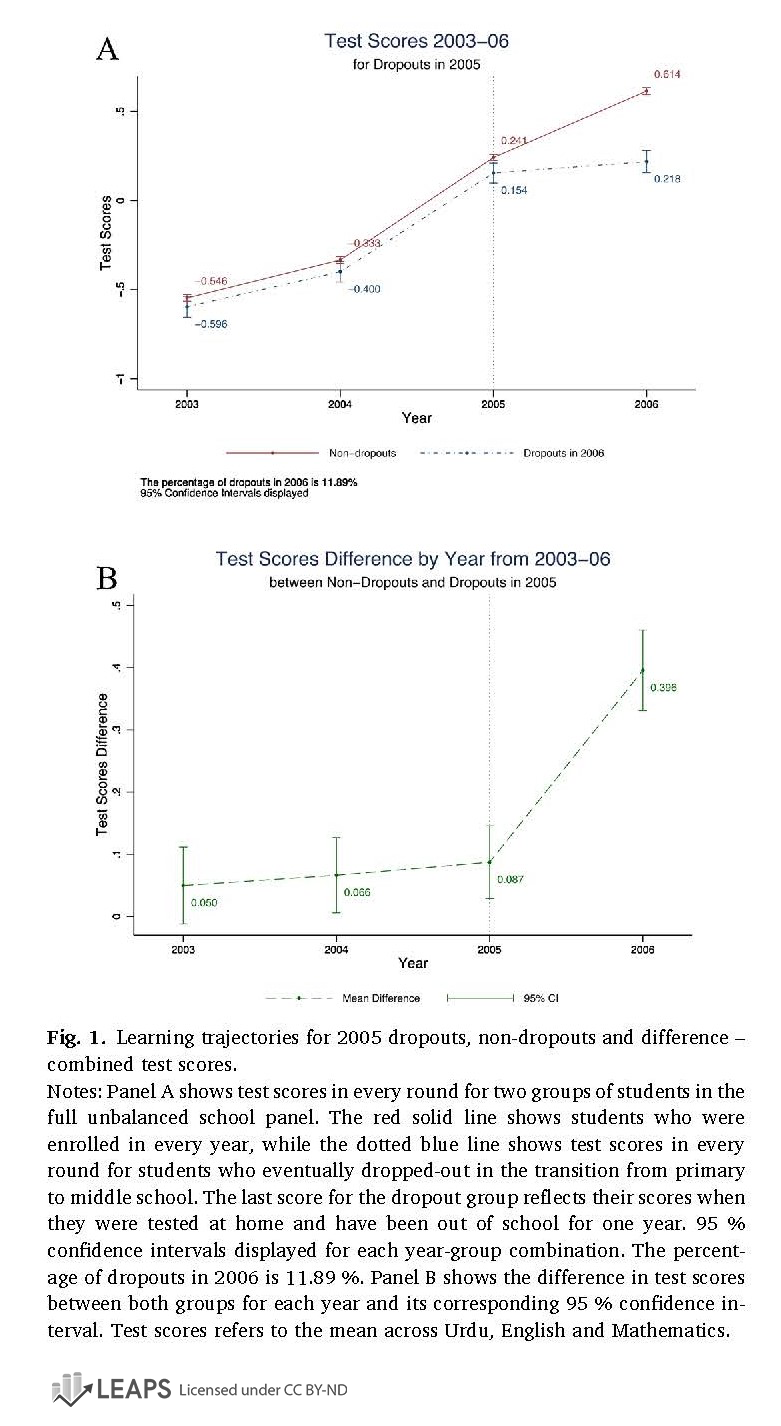

For children who drop out of school after grade 5, learning gains between grades 3 and 5 were identical to children who did not drop out

One question is whether this learning is due to schooling as opposed to natural gains as children age. To distinguish learning due to aging versus schooling, we tracked and tested children who had dropped out between grades 5 and 6. While dropouts reported slightly lower test scores in previous grades than children who continued in school, learning gains between grades 3 and 5 were identical for dropouts and non-dropouts. However, once children dropped out, their learning stalled, while for those who remained in school it continued along the same trend. So, learning gains observed through the years are due to schooling (not aging) and a narrative suggesting that dropouts would not benefit from schooling anyway needs to be revisited. Our results suggest that if test score gains have constant returns for adult outcomes, dropouts and non-dropouts would experience similar returns from remaining in school.

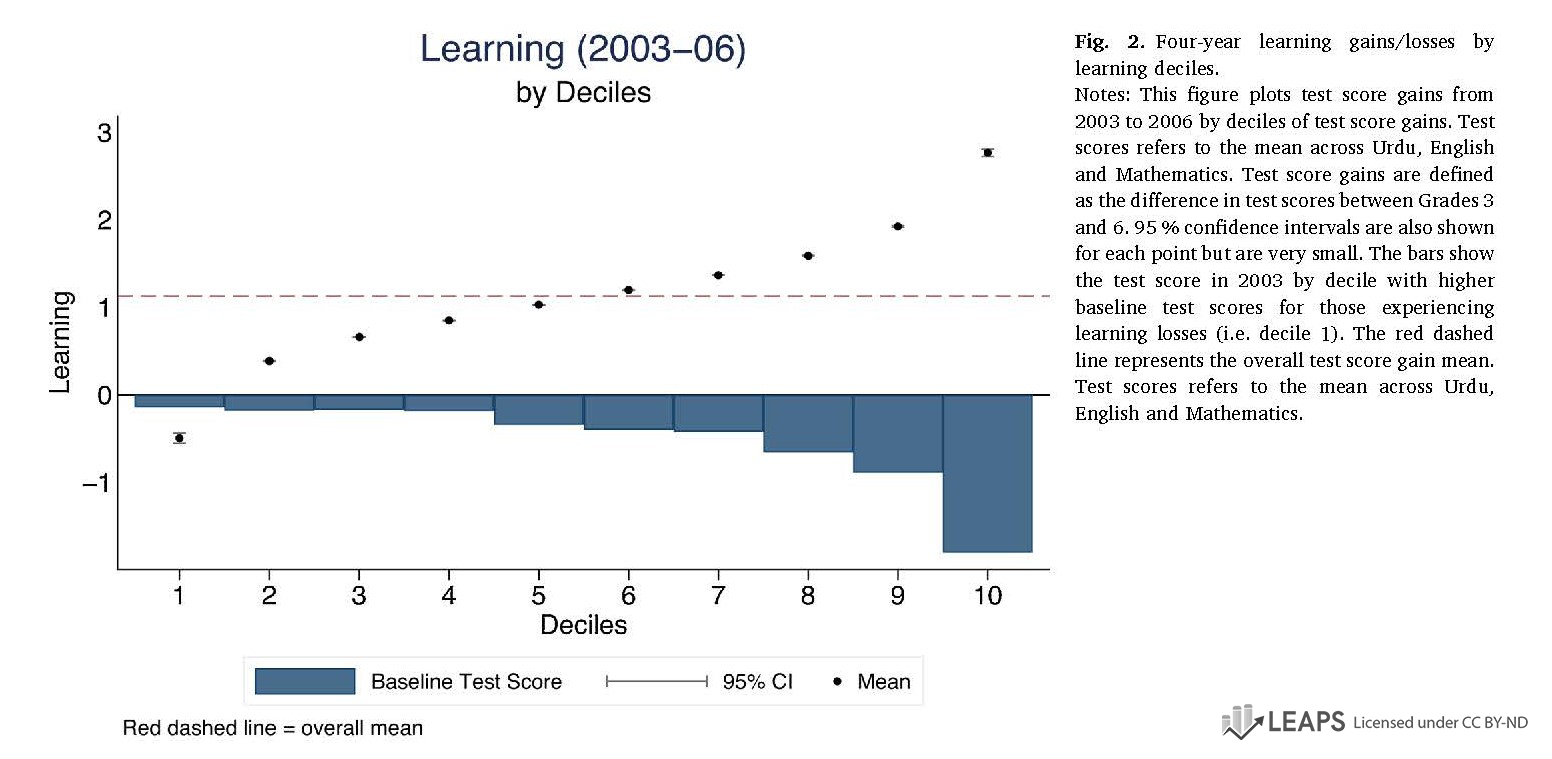

Children whose test scores were in the bottom 20% learned significantly more than children ranked in the top 20%

We next consider whether low learning rates are driven by less-prepared children (with ex-ante lower test scores) falling further and further behind. We might expect these children to experience more mismatch between their academic preparation and the curriculum, leading to lower levels of learning. Surprisingly, this is not the case. Children whose test scores were in the bottom 20% in grade 3 learned significantly more between grades 3 and 6 than children ranked in the top 20%. Correcting for mean reversion in test scores does not change the qualitative pattern. In fact, we see a marked convergence in test score levels, rather than divergence, over time. Schooling reduces inequality in learning.

In LEAPS, as in most settings, test scores are not highly persistent across years. One extreme consequence of low persistence is that learning trajectories are not monotonically increasing for all children or all questions. We propose a new term for the patterns in the data: ‘fragile learning.’ Children learn in one year but are about as likely to forget as to consolidate their learning. In fact, the proportion of ‘fragile learners,’ or those who learn and then forget (and then sometimes learn again), is worryingly high. The key message is that performance in school has as much to do with forgetting as it does with learning.

The basic facts are that children learn, schools tend to equalize test scores and a conflagration of factors lead to dropouts, not just how much children are learning. Further emphasizing the importance of schools vs. household characteristics, our paper shows that household characteristics, such as parental wealth and education, only account for 6% of the variation in year-to-year learning gains. Schools really matter, and if we can keep children in school longer—even with the status quo — children will be better off in terms of what they know.

Study Resources

The following resources are for public use in presentations, papers, lectures, and more under the Creative Commons license BY-ND. Click the images below to view or download individual images, or use the button to download all.

As a condition of use, please cite as: Bau, Natalie, Jishnu Das, and Andres Yi Chang. 2021. "New Evidence on Learning Trajectories in a Low-Income Setting". International Journal of Education Development, 84: 1-26.